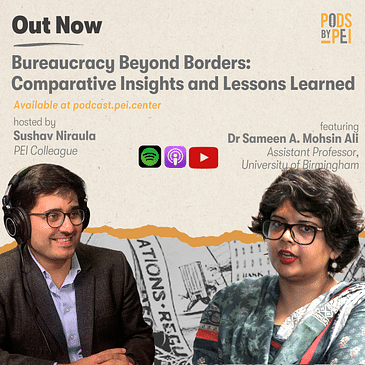

Ep#108

Dr. Sameen A. Mohsin Ali is an Assistant Professor of International Development at the University of Birmingham. Her research focuses on the impact of bureaucratic politics on state capacity and service delivery. She is particularly interested in the dynamics of bureaucratic reform, the implementation and impact of donor programs, and the intersection of party politics, citizens’ interests, and bureaucratic incentives. Exploring cases from Pakistan and Nepal, Sushav and Sameen delve into the dynamic relationships between politicians and bureaucrats. In doing so, they imagine bureaucracy in a decentralized context, discuss ways of navigating bureaucratic embeddedness, corruption, and efficiency, and explore how to plan bureaucratic reforms. The conversation offers a nuanced perspective on the complexities of governance and the critical forces that shape public administration in developing countries.

Like listening to PODS?

We’d love to hear your thoughts and reviews on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, YouTube, or wherever you listen to the show! You can also follow us on Twitter at Tweet2PEI, and on Facebook and Instagram at policyentrepreneursinc for updates on the latest episodes and share to help us reach more enthusiasts. If you liked the episode, hear more from us through our free newsletter services, PEI Substack: Of Policies and Politics, and click here to support us on Patreon!!